In his essay “Bitcoin’s Existential Crisis”, Nic Carter describes the identity problem that is inherent to Bitcoin. Because no one has the authority to give decentralized systems an identity, they rely on intersubjective consensus around a set of practical core values.

You can think of these core values as the lowest common denominator between all people in Bitcoin, and I tried to formalize them in Unpacking Bitcoin’s Social Contract – with the caveat that any such attempt is necessarily both highly subjective and chasing a moving target.

When people disagree about what Bitcoin is or should be, that can impact the real world in two different ways. For one, there is an unspoken rule that the protocol won’t be updated unless virtually all important stakeholders are satisfied with the proposal. When people disagree over basic principles, no major proposal can ever get the buy-in of all necessary parties. We call this “protocol ossification” and most people seem fine with it today because (1) Bitcoin doesn’t really need to change much from here, and (2) that resistance to change is seen as a valuable property that sets it apart from centralized systems of the past.

But there’s also the risk that some external event occurs that requires Bitcoin to change, whether in response to an attack or bug or more generally due to a lack of success in the market. In that case, the same governance gridlock can quickly become an existential issue as the community fractures into opposing sides.

Mutually exclusive narratives can coexist with each other for some time, but eventually they reach their boiling point. That was the case in Bitcoin with the collision of “Bitcoin is for cheap payments” vs. “store of value” and in Ethereum with “code is law” vs “social consensus is law”. Both sides had just as much a credible claim to being right, because there is no central party to „tie-break“ their disagreement. The only way these conflicts resolve is via messy social consensus formation, market signals, and in some cases, permanent community splits.

The biggest questions today are probably how to address possible incentive problems due to the declining block subsidy, and how private Bitcoin should be in the wake of increasing blockchain surveillance. Nic and I tried to account for these and other possible narrative collisions back in our article Visions of Bitcoin.

As Nic puts it, „systems with more internal consistency and more universally agreed upon value sets are better equipped to last.“ That suggest the optimal social contract

(1) has a very small number of rules (to include as many people as possible)

(2) that users are highly committed to if something ever goes wrong with the software.

In today’s article, I want to build on this existing body of work by exploring where real bitcoiners actually draw the line in terms of their core values, where their logic might reveal potential narrative collisions, and what all this means for Bitcoin’s future.

Introducing the questionnaire

In order to explore this topic, I employed a basic questionnaire to ask my Twitter followers what they see the core values of Bitcoin. The way I framed the questions was to ask for the negative – what changes or events would make Bitcoin no longer Bitcoin to them? The implication here is that users would be bothered enough to sell their coins and leave the project.

All questions can be grouped into these five high level topics:

- Censorship-resistance;

- Intermediation;

- Monetary inflation;

- Settlement guarantees; and

- Means vs. ends (more on that later.)

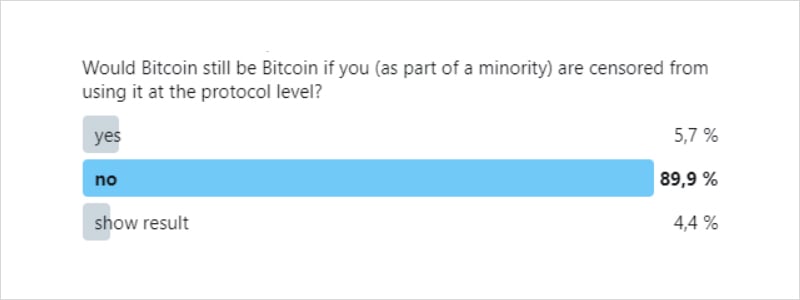

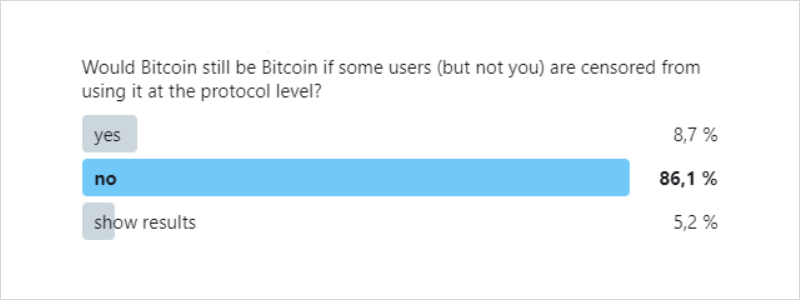

Censorship-resistance

The first topic I asked about was censorship resistance, which has always been one of the core tenants of the Bitcoin social contract. And indeed the results came in like expected: People really value censorship resistance, both for themselves and others, to the degree where it can seem irrational to bystanders. After all, people don‘t stop using Paypal because it has deplatformed legal arms dealers or political dissidents, or leave Twitter after it has censored many a conservative media organization or politician.

This only goes to show that Bitcoin actually *has* a social contract, and people feel disproportionately more violated if censorship happens in Bitcoin than in other systems where they might have come to expect it, even when they are not personally affected.

Indeed, Bitcoin’s design makes censorship very unattractive because if one miner doesn’t include your transaction, the next miner might, and as a result they will make more money in the long run. This holds true unless one miner (or coalition) controls over half of the hashpower and can safely ignore any non-compliant blocks from other miners. It also works with less than half of hashpower if the attacker can credibly scare other miners out of including transactions or addresses that are on a public blacklist (see “feather forking”).

The fact that users aggressively signal that they won’t accept others being censored actually matters to that, if the counter-threat can make it unprofitable for miners to follow the feather-forker. It is also a counter-argument to the popular thesis that only transaction fees and not the block subsidy protect Bitcoin from censorship, as the attacker stands to lose business from uncensored parties as well.

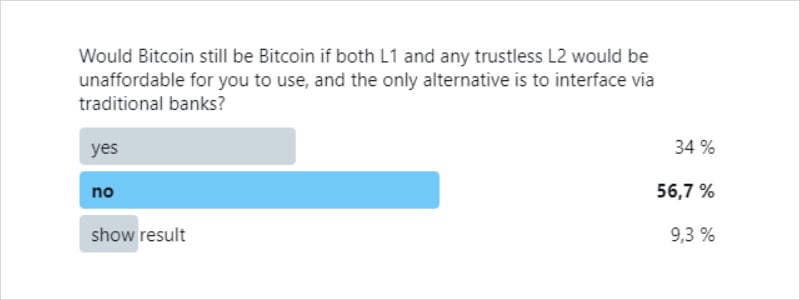

Intermediation

If people are censored from using Bitcoin, this could only really happen in two ways: 1) on the consensus layer by miners, or 2) on the application layer by trusted intermediaries.

Bitcoin is often said to eliminate said trusted third parties, but that applies only when users interact with Bitcoin directly. If most activity happens through trusted third parties, we could see the same encapsulation of a trustless base asset in a trusted wrapper by that eventually led to the failure of the gold standard. For a thought experiment of why intermediation is a big risk to bitcoin, see Why Bitcoin might not survive a Bitcoin Standard.

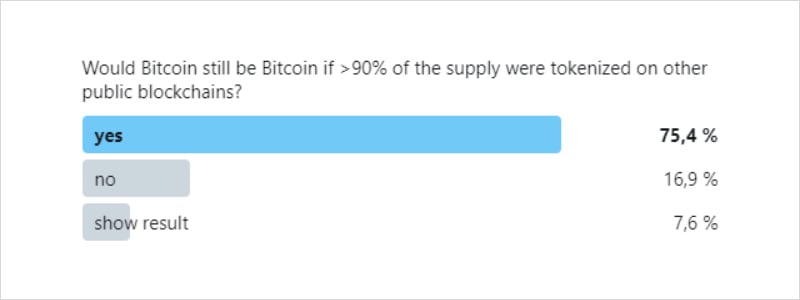

Given the aptness of bitcoiners for pointing out gold‘s weaknesses, I expected tolerance for a fully intermediated Bitcoin to be very low. But alas, I was surprised by how many people would be a-okay with it. Maybe they are simply pragmatic because Bitcoin indeed can only support so many base layer and LN transactions before fees would price out most smaller users and transactions, and most people might not think of themselves as “rich enough”.

That said, there are good reasons why the worries about an intermediated Bitcoin could be overblown and Bitcoin could fare better than gold has, due to its unique advantages. Because Bitcoin is a digital bearer asset, anyone from anywhere in the world can create a new Bitcoin bank that doesn‘t necessarily have to comply with local regulations. And why intermediaries would still be trusted, there would be more competition between them, putting the customers in a better position than if regulation protected incumbents from disruption. Because Bitcoin can be transferred so easily, this would also make it easier for customers to switch between different intermediaries, further lowering the exit cost.

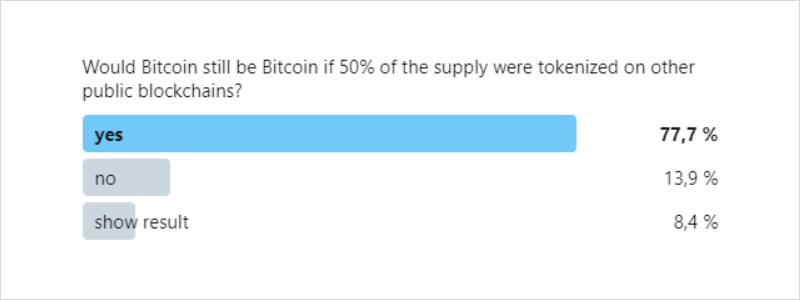

In spite of being generally skeptical of other non-Bitcoin blockchains, it also seems that Bitcoin users appreciate the benefits a blockchain provides in terms of transparency and validity over the black box that is traditional banking.

I think that this trend is likely to continue, as we‘ll see different trust models, from fully trustless (TBTC) to secured by majority of hashpower (Drivechain) to secured by a consortium (Liquid) to secured by single custodian (BitGo) for users to choose from.

Monetary inflation

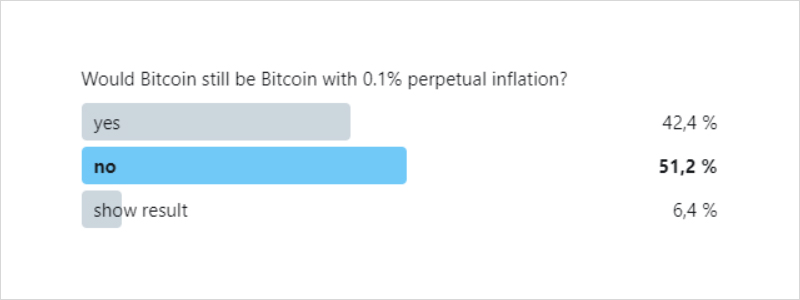

The easiest way to trigger my fellow Bitcoin friends on twitter is to entertain – even with many caveats – the idea of adding some kind of monetary inflation. Hence I thought that this dislike of inflation would be reflected in the responses, but came out quite surprised.

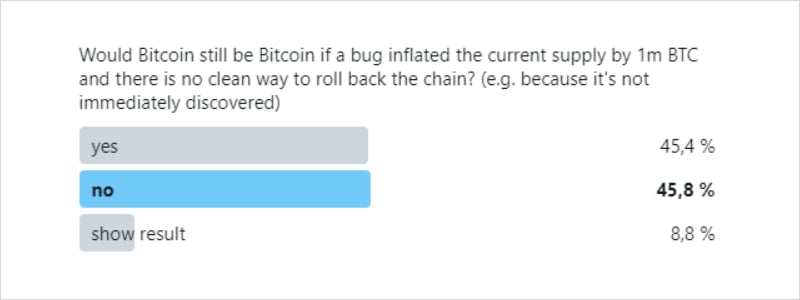

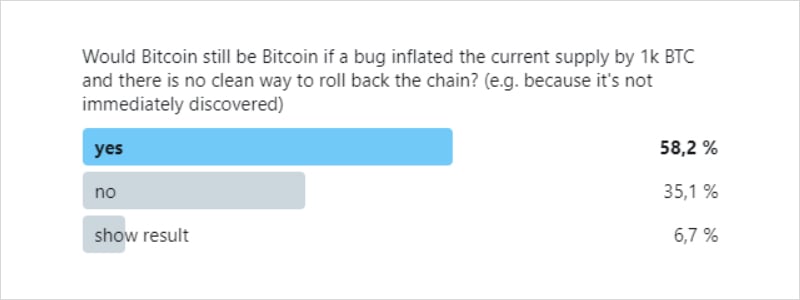

I went ahead and first asked about “accidental inflation”…

…followed by the kind of deliberate inflation that is often proposed as a solution to paying miners if L1 fee revenue turns out to be insufficient.

It seems that many people are willing to accept inflation if it is accidental – even if it is substantial (+1m total supply!) – but are far less tolerant for deliberate inflation.

This requires some discussion, as it could seem irrational at first. At 0.1% monetary inflation, it takes 48 years to create the same 1m BTC and yet more people would rather reject a version of Bitcoin with a tiny bit of tail inflation than one that has the same 1m BTC immediately. Even though the tail inflation makes Bitcoin more secure, while the accidental inflation would not!

We know there are many people in Bitcoin who value scarcity and Bitcoin’s 21m cap a lot, but it seems they are also pragmatic about it. If a bug has inflated the supply, then the damage is already done, and – assuming the bug is fixed – that does not necessarily make another inflation bug any more likely. Whereas if we deliberately agreed to inflation, it might feel more like a betrayal to the core values rather than a mistake at implementing them.

One thing that often annoys me is people’s fixation on monetary inflation over price inflation. The first is the increase of Bitcoin’s supply, the second is a decline of bitcoin’s purchasing power. The reason it seems so short-sighted is because supply inflation ignores half the market – the demand side for Bitcoin!

To give a very simple thought experiment, if supply inflation was the only thing to optimize, we could change the protocol to stop issuing more coins starting tomorrow. But the purpose of Satoshi’s distribution schedule was not simply to limit supply inflation but 1) to give more people the chance to buy or mine Bitcoin, and 2) to pay for miner security until the blockspace market has come of age.

A bitcoin without the block subsidy would not be secure today and its price would likely falter as a result of this insecurity. This alone proves that supply inflation can be positive for the price and hence the purchasing power of holders. It simply depends how much the market values sustainability and long-term predictability.

As a counterargument to my own thesis, I would like to once again offer Nic’s thesis that a social contract should be as simple and consistent as possible. “We should optimize Bitcoin’s price” is how most people actually behave, but it’s much more abstract and subjective than “We should keep Bitcoin free of supply inflation”. So maybe in practice, the best thing is to converge on the less accurate and useful more objective and verifiable choice of limiting supply inflation, not price inflation.

Settlement guarantees

Moving on to Bitcoin’s settlement guarantees, I was quite interested in the responses we would get. Both because I’ve locked horns significantly with the Bitcoin community over this topic but also also because unlike inflation or censorship, the settlement guarantees are something that is experienced very directly by everyone who transacts with Bitcoin.

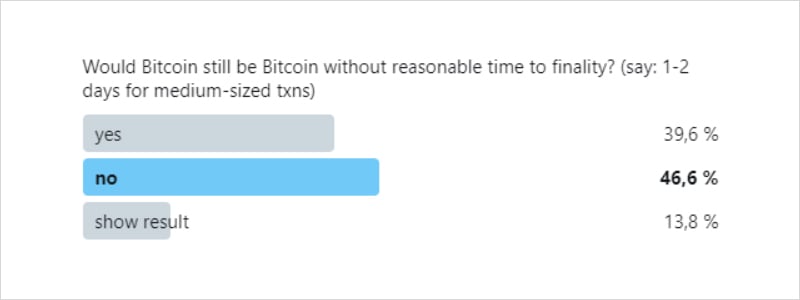

More than half of respondents find a Bitcoin that takes days to settle no longer useful. I do see that as a blow to the popular argument that miner rewards can never be too low in the future as users will simply wait many blocks for settlement (advanced by Nick Szabo and others). This argument ignores that Bitcoin competes with other solutions in a competitive market place for money, and while it can afford to have worse efficiency in return for better scarcity and censorship resistance, there is a limit to how much worse it can be.

That said, more people than in any other question chose “show result”, indicating a high degree of uncertainty.

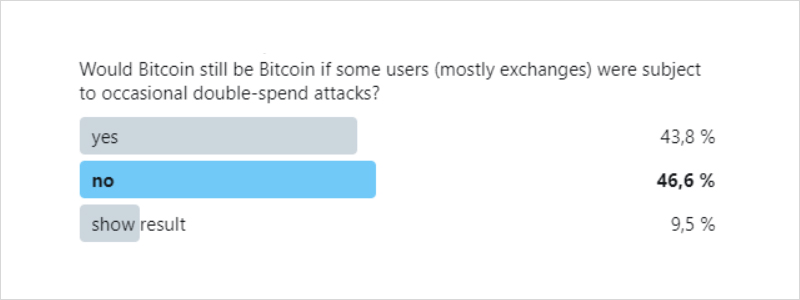

Around half of respondents draw the line at double-spends, which makes sense in a system that values property rights above else. But if we think about this, double-spending is basically like bouncing a check or reversing a credit card transaction. Does the fact that some people bounce their credit card transactions make it useless as a system, especially considering that users themselves would basically never be victims of this, only exchanges and large merchants?

Maybe the same logic applies here that we discussed in the context of censorship resistance, where – unlike a credit card – Bitcoin transactions are intended to be “eventually final”, and hence any violation feels more like an attack on the system as a whole.

That said, the other half of respondents would keep using Bitcoin even when there are occasional double-spends, and I think that is a much healthier attitude. if Bitcoin users wanted absolute safety from this attack, then it would mean that

- they would have to spend more on security than a Bitcoin where occasional double-spends are accepted. Depending on the development of the blockspace market, this view could eventually collide with the “no inflation” view, in which case one of them would have to lose and there might be a community split. If we want to prevent that, loosening your standards in favor of a “lesser evil” can sometimes go a long way.

- Users would have to be prepared to reject more reorgs with social coordination. Doing that in an efficient way requires procedures and hierarchies (think: leaders) to be put in place that make the system less socially scalable.

In summary, I think that users‘ preference for fast and reliable settlement and their preference for no monetary inflation are the most likely (but still not likely in absolute terms) to collide.

Means vs. ends

To conclude the questionnaire, I wanted to ask about a few deliberately random aspects of Bitcoin that are *not* tied to its core values. The goal here was to see if people can identify the difference between the ends – our goals for Bitcoin as a system – and the mechanisms (means) that implement them.

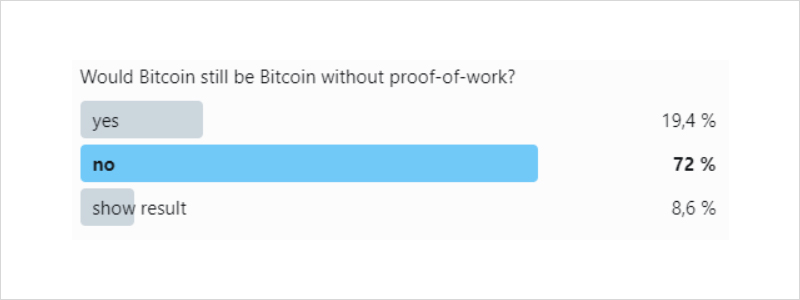

As maybe the biggest surprise of the entire questionnaire, almost more people draw the line at “Bitcoin has proof-of-work” than “Bitcoin has a fixed supply”. As I’ve argued many times before, I see Bitcoin as a set of goals and shared rules, a social contract, and that we build software to automate this social contract. In 2008, Satoshi identified proof-of-work as a key part of solving this puzzle. But it doesn’t mean that PoW is itself one of these goals or core values of Bitcoin.

Source: Unpacking Bitcoin’s Social Contract

Instead, proof-of-work is a mechanism to implement two specific goals:

- The trustless distributed time-stamping of transaction – a decentralized clock

- Distributing coins initially in a fair and trustless manner

If any other mechanism ever succeeds at implementing these goals better, and is as battle-hardened as PoW, or if a major vulnerability is detected in PoW, then I would not be opposed to replacing it. But maybe it’s not surprising that the community takes a much stronger stand on the mechanism of PoW than any other, as – with more and more proof-of-stake networks coming online – people “want to give no ground to the enemy here”.

To clarify, I do not think that Bitcoin has anything to fear from PoS coins on a purely fundamental basis, but the arguments given in the favor of PoS (more green, no risk from China, attackers can be identified and slashed) have powerful narrative-value, and I think most bitcoiners are at least subconsciously concerned about that.

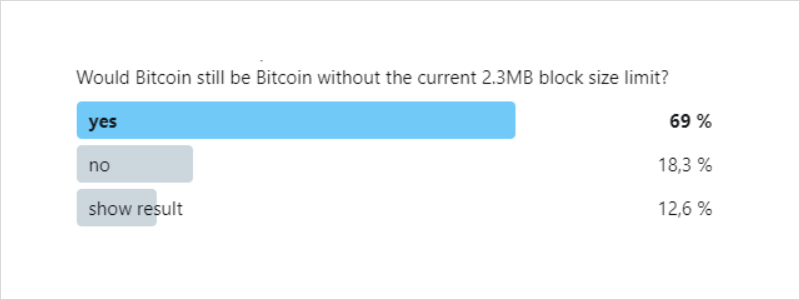

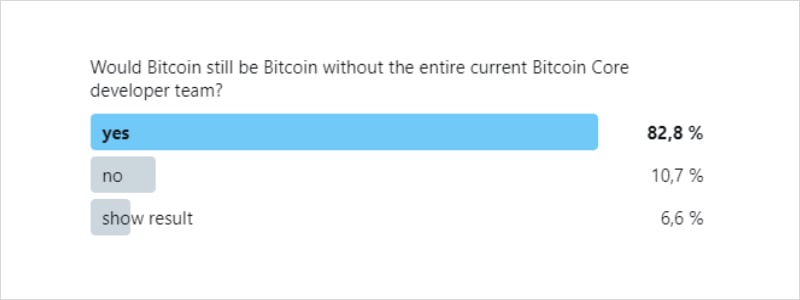

As for the other two questions, the answers are much more in line with what I expected, with people identifying that the current block size limit or the current core development team are not “means” in itself but “ends” to the “means” of implementing Bitcoin’s core values into a technical protocol.

For example, the block size limit is needed to ensure that Bitcoin remains affordable to use for full nodes, who have to validate the entire history of the blockchain and then stay in sync with all incoming blocks as well. It is also important to ensure the scarcity of block space as the block subsidy expires, so transactional demand from users leads to sufficient fee revenue for miners.

Bitcoin’s veto-based governance

Something I really want to point out is how every question had many people “draw the line” and say “this is not Bitcoin for me”. One the one hand, this confirms that we indeed correctly identified Bitcoin’s core values. On the other, it nicely explains why

- there is so little progress in Bitcoin’s protocol development (it’s so hard to get consensus on anything)

- it’s very hard to introduce potentially dangerous changes into Bitcoin. The latter makes Bitcoin very reliable for businesses and developers to build on.

Source: Twitter

Of course the answers here are not necessarily indicative of how someone would vote with their wallet at the end of the day and I suspect that – more than everything else – bitcoiners who stuck with BTC during the scaling wars care about being in consensus with as many other people as possible to protect Bitcoin‘s network effect.

If you’re like me, you might think that we should protect Bitcoin’s long-term sustainability by discussing such options as a security tax or supply inflation today – of course without activating them before it provably becomes a problem. But even though this isn’t communicated anywhere, I think most people’s initial reaction to such discussions is that they see them as slippery slopes.

The idea of a slippery slope is that a chain of itself innocuous events could lead to some eventually very bad change, such as the slow erosion of Bitcoin’s anti-inflation values. In order to prevent a slippery slope from happening, bitcoiners create Schelling fences – a concept which actually explains quite well what we are seeing today.

On schelling fences and social signaling

A Schelling fence (first introduced by Scott Alexander) is a Schelling point that people make a credible precommitments to defend – almost like a binding contract with themselves. Maybe the best example most of us would be familiar with is to never even smoke the first cigarette, because you don‘t know what it will do to you.

To return with to the example of inflation, the slippery slope argument would be that if we normalized the idea of 0.01% tail inflation today, we might also eventually accept the idea of 0.02% tail inflation, and so on, until Bitcoin has become indistinguishable from fiat money. Because we can’t trust our future selves, we commit to never even entertaining the idea of inflation, even if that means going down with the ship.

Creating these precommitments serves as the first line of defense to negative changes to Bitcoin, but it also serves more functions beyond that:

- Users constantly signal their precommitment to other bitcoiners, both to verify that they are still on the right track as well as to strengthen the shared commitment with the rest of the tribe.

- During attacks or other bad events, it’s important that everyone already “knows the drill” because they have a precommitment to the values they want to defend and how.

- There is tremendous value in making that intangible precommitment tangible to newcomers. The more people who are less familiar with Bitcoin’s lore and history can rely that the existing community is hell-bent on defending Bitcoin‘s core protocol values, the more safely they can hold and use and build on Bitcoin at the end of the day.

Caveats to this analysis

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention several caveats that are inherent to any such “social science” experiment.

- An analysis like the one I did today is incredibly subjective and shouldn’t be seen as something that represents the diverse views of the Bitcoin community, most of whom are not my Twitter followers.

- The problem with polling current holders is that they’re a minority of future users if usage actually picks up, who might hold very different views of what Bitcoin should do and where the Schelling fences should be put. This is akin to the argument that all strongly libertarian leaning people in the world are already in Bitcoin, so the marginal person who joins Bitcoin tomorrow is bound to be increasingly less ideological about its values and more focused on its every-day use value.

- While people can be allergic to intentionalism, Satoshi left us a lot of “originalist” literature of what he intended Bitcoin’s social contract to be. Whether bitcoiners stick by what Satoshi had planned is a different matter, but the intentions of its creator are at least a strong natural Schelling point.

- Bitcoin is not a democracy, and most peoples’ votes don’t matter. At the end of the day, most of us are here because we believe that the free market can produce a better money than governments can. Most of us are not smarter than the market, and ultimately listen to what the markets want. So if we do end up getting a clash between two mutually exclusive core values in Bitcoin, I could imagine that most people will continue to ride with what the market sees as most valuable (e.g. in the form of fork futures or prediction markets) and use that to inform their own views.

(1) The logic is that a censor always earns the block subsidy, but only the fees of uncensored transactions. I want to link to Eric’s Voskuil’s post on the matter, but Libbitcoin.org seems to be down right now

AUTHOR(S)