What if the age of central banking is still ahead of us?

Maker is a central bank that actively conducts monetary policy in the same way existing central banks do. We’ll show this by analyzing Maker’s options in Dai’s deflationary mini-crisis. Connecting the dots between Maker and incumbent central banks like the Federal Reserve allows us to study the cause and effect of monetary policy choices on a micro rather than macro scale. Algorithmic central banks, made possible by smart contracts and trustless collateral, promise a bright future for discretionary monetary policy.

Dai after Mar 12th – a case study

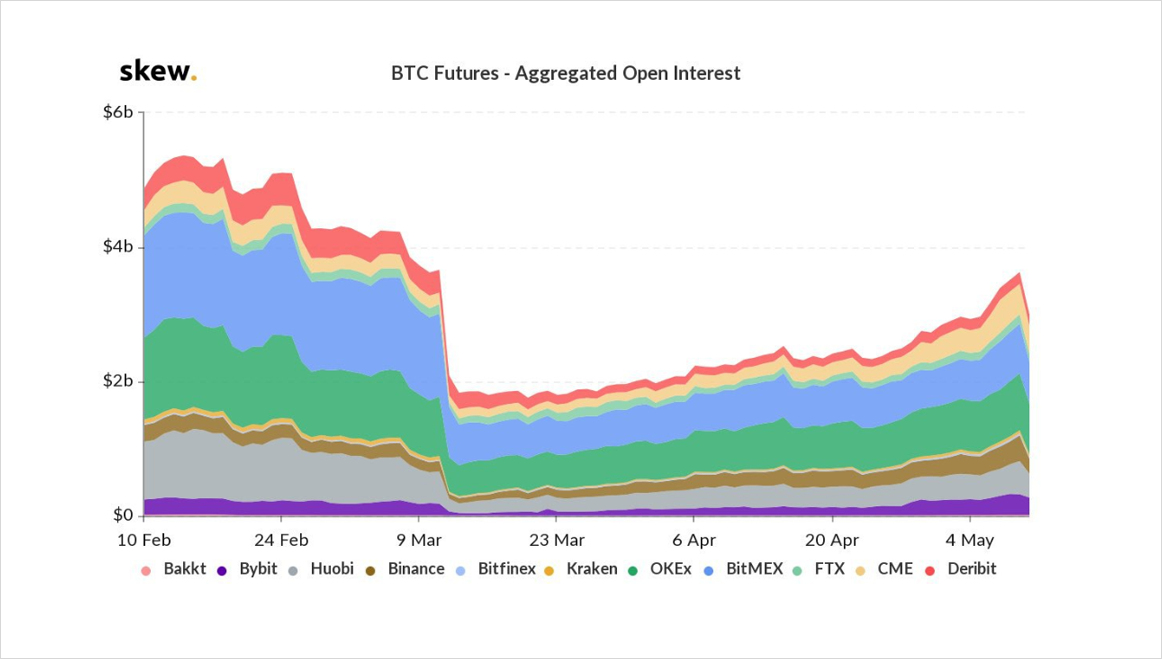

On March 12th, 2020, also called “Black Thursday”, Bitcoin’s price dropped over 50% from peak to trough, structurally led, and amplified by BitMEX. Most of the leverage evaporated from the market.

Source: Skew.com

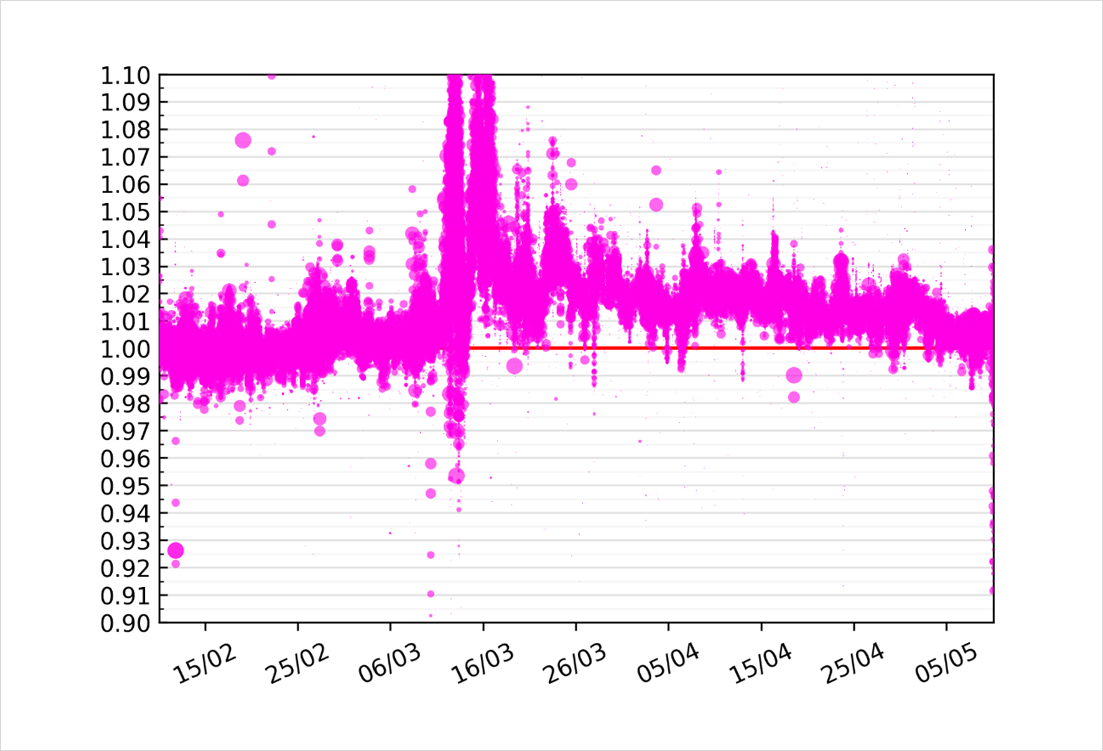

Bitcoin trades near $9k again as we speak, higher than before the crash, but the scars are felt in reduced open interest as well as in the object of this article: Maker’s stablecoin Dai. Supposed to be pegged to one dollar, it has traded at a premium for almost two months and is only slowly returning to its target price.

Source: dai.stablecoin.science

Stablecoins have risen immensely in popularity as they provide a low-cost way for traders to derisk their portfolios during market stress. Especially in high-stress events like Black Thursday, the safe-haven attributes of stablecoins can warrant a significant price premium as traders bid up the price past a dollar.

Arbitrage in dollar-backed stablecoins vs Dai

For fiat-backed stablecoins, this price increase signals arbitrageurs to send fiat to the issuer in exchange for more stablecoin tokens. They then sell these tokens at the current market premium to harvest the basis spread. They continue doing this as long as the spread is larger than the cost of converting more fiat, which happens when the stablecoin trades very close to a dollar again.

As we have explained in another post, this arbitrage cycle does not work for Dai which has to be drawn against an overcollateralized debt position. The cycle does not close when the arbitrageur sells the Dai, as he still has extra collateral in the system. That extra collateral incurs both a volatility cost and a capital cost that isn’t present in fiat backed stablecoins.

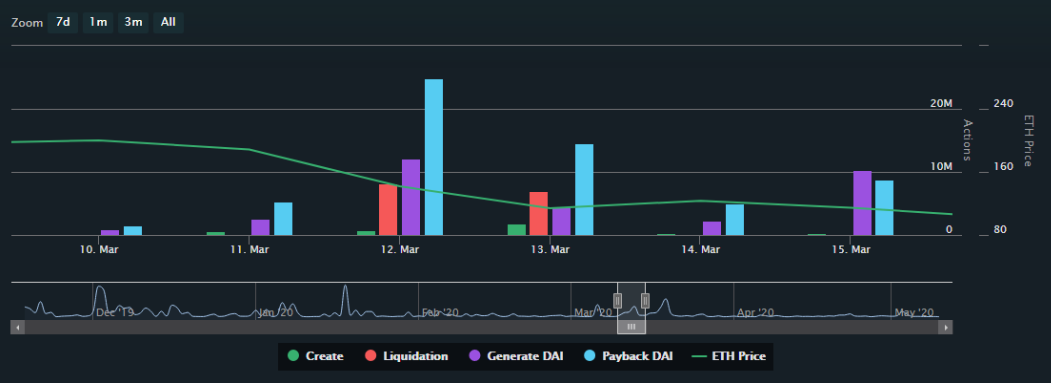

Worse, Dai actually works against the market in times of high stress, as excess demand for Dai from traders seeking a safe haven is met by a margin call on CDP owners. As the value of their collateral depreciates, they need to either top up collateral or pay down some of their Dai-denominated debt to prevent liquidation. As a result, the supply of Dai decreases in moments of market stress when the demand for Dai is the highest.

Source: defiexplore.com

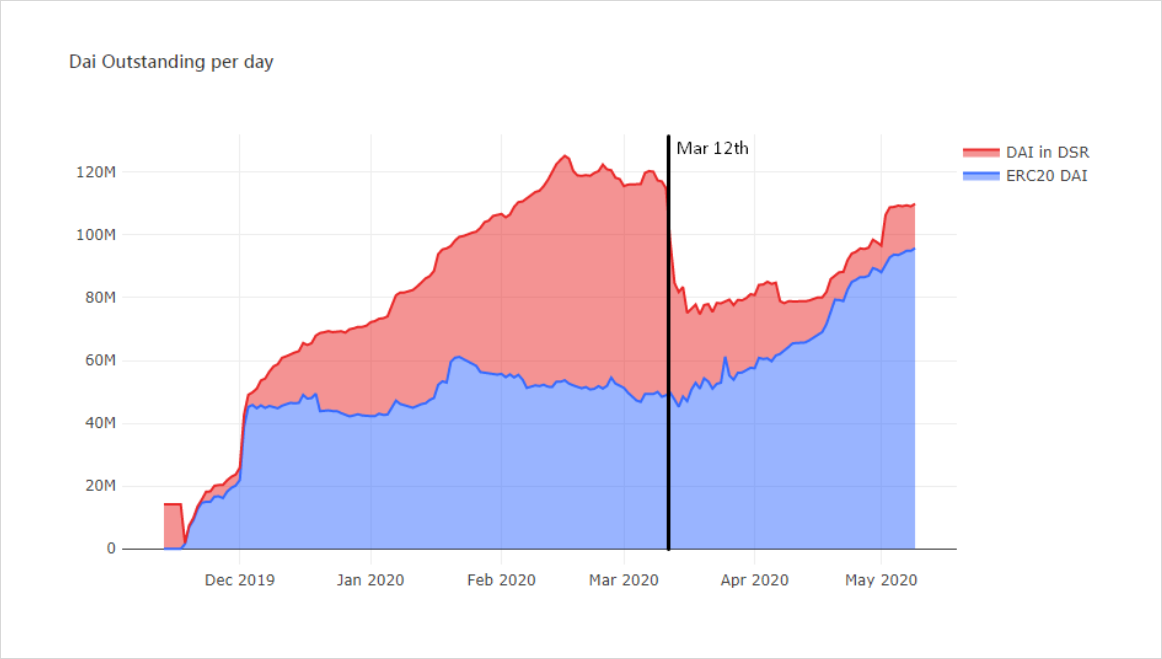

Source: explore.duneanalytics.com

Maker’s policy options

Since arbitrageurs cannot stabilize the price of Dai on their own, the system actively conducts monetary policy to support the peg. To my knowledge, it can do so in three ways.

1) Changing the price of money

Maker charges borrowers a Stability Fee (SF) on the amount of Dai that they draw. The borrowers then sell that Dai for something else, e.g. more ether. They later need to buy back Dai on the market to pay down the debt, so they represent the short side of Dai.

On the long side, you have the people who hold Dai, e.g. to derisk their portfolio. These holders can also earn the Dai Savings Rate (DSR) by wrapping the tokens in a specific contract (the receipts for which are called Chai and are themselves tradeable).

The SF and DSR are two sides of the same coin. Together they form one mechanism where payments are made between Dai holders (the longs) and CDP owners (the shorts), at the discretion of the Maker operators (who also take a small cut). So the SF funds the DSR or vice versa, depending on market conditions.

If this reminds you of the funding mechanism of derivatives exchanges, you are absolutely correct. This is the same method that BitMEX, Deribit, OKEx, Huobi, etc. use to peg the value of their perpetual inverse swaps (that never expire, hence the name “perpetual”) to the value of the underlying spot markets.

However, Maker did not implement this mechanism properly so far. When Dai trades below a dollar, there’s too much demand from CDPs (shorts) and too little demand from holders (longs). In that case, Maker can increase both the SF and DSR, forcing borrowers to pay holders for the privilege to borrow. Maker’s problem occurs when Dai trades above a dollar, as it does today. There is currently too much demand to hold Dai, so Dai holders should pay borrowers until the balance is restored.

The way Maker works right now this is impossible, as participation in the DSR is voluntary. When asked to pay a negative rate in the current architecture, holders would simply withdraw their funds from DSR. So first, the DSR has to be made mandatory, before it can be allowed to go negative. The change would not be without tradeoffs, as other applications would have to change the way they interface with Dai.

A similar proposal is currently discussed in the Maker forums that would implement negative rates via a floating peg. This target rate feedback mechanism (TFRM) would also make the DSR non optional, just in a roundabout way. The fact that there are different viable paths to implementation show that the hurdles that prevent negative rates from being adopted are not mainly technical but rather mental in nature.

2) Changing credit requirements

To recap, to get the price back down Maker either needs more Dai in circulation or less demand to hold Dai. They exhausted their first mechanism by setting both the SF and DSR to zero, but it did not have the desired effect yet. When even a 0% SF does not incentivize the creation of more supply using ether collateral, there is also the option to loosen credit requirements. They can do this in several ways.

First, Maker could allow existing CDP owners to borrow more Dai against their collateral. They would do this by loosening the Collateralization Ratio (CR), for example from 150% currently to 140%. Borrowers could then generate more Dai from the same amount of collateral. This comes with the tradeoff that during market stress, the system has a smaller safety margin and a larger risk of becoming insolvent.

Second, they could allow more types of collateral, and this is so far the primary route chosen. Maker has recently added USDC, WBTC, and BAT, allowing those to be used as collateral alongside ether.

Especially USDC deserves our attention here. If you look at the arbitrage cycle discussed earlier, the reason Dai cannot be arbitraged the way that USDT can is that arbitrageurs are stuck with excess collateral in the CDP. However, if a type of collateral had a CR of 100%, there would be no excess. In practice, no asset is 100% risk-free. A cryptocurrency like ether is no one’s liability but is volatile against the dollar. USDC is stable but could be frozen by law enforcement. Maker operators know that Dai is only as good as the collateral backing it, so they currently set a conservative CR of 120%.

3) Open market operations

Finally, Maker could directly intervene in the Dai money markets. In an open market operation, Maker would mint Dai initially without backing and use it to buy up assets like MKR or ETH on the open market. These assets would then back Dai and the system remains solvent. At the same time, the supply of Dai in the system increases, hopefully creating downward pressure on the price of Dai. Maker has not (to my knowledge) conducted any open market operations before and may not have the architecture in place, but same as negative interest rates they are another promising option for the future.

Parallels between Maker and central banks

I gave you a long-winded explanation of how Maker is thinking about the current mini-crisis their stablecoin is in. The goal was to show how similar the current situation of Dai is to the situation of fiat currencies all around the world.

- Dai persistently trading above a dollar (their price target) is the same as fiat currencies consistently missing 2% inflation against a basket of consumer goods and services (their price target). Both are trying to create inflation right now – only against different targets!

- Maker lowering SF and DSR to zero is the same as central banks setting interbank interest rates to zero.

- Both systems struggle with the implementation of negative interest rates. Central banks struggle because bank accounts are optional; users can withdraw their balance and use cash instead. Maker struggles because the DSR is optional; users can withdraw their tokens from the contract and transact in Dai instead of Chai.

- Maker’s new collateral types resemble subprime collateral for mortgages.

- Finally, the open market operations I described for Maker are the same for central banks – in fact, you might recognize them under the name quantitative easing (QE).

Looking at these parallels can create more clarity about what actually motivates central bank decisions – because we are running our own central bank experiments right now, on a much smaller scale.

Take for example negative interest rates. Somehow it seems crazy to most of us that interest rates in the US could become negative. We feel violated, and we also feel like something in the system is broken. Then we log into our BitMEX account and a negative funding rate is the most normal thing in the world to us. Yet, the two are actually one and the same. Interest rates are a stabilizing mechanism where longs pay shorts or shorts pay longs, depending on how far one Dollar, one Dai, or one contract of XBTUSD is removed from its target price.

I think a key difference is the perceived legitimacy of their respective mandates. Maker’s mandate is to keep Dai at a dollar. Central banks have a dual mandate of a) full employment and b) general price stability. The Fed tries to slowly devalue the dollar against a basket of consumer goods and services (measured by the CPI) at a rate of two percent annually. Some people disagree that the target should be 98% of CPI. Others disagree that the CPI accurately represents inflation in the first place, as the basket composition itself is subject to human discretion.

Maker has it much easier. People generally agree on what a Dollar is or how that should be measured. Dai holders don’t feel disappropriated when the price returns from $1.02 to $1.00, because they also expected this to happen eventually.

The future of money could be discretionary

So far, we used Dai trading above a dollar to show that Maker conducts monetary policy and that it uses the exact same tools as central banks. Is there a takeaway from this?

One insight is that Maker operators can learn from the existing body of literature and knowledge on the topics of monetary policy. But observers can also learn about the workings of real central banks by looking at cryptosystems like Maker, where the policy decisions and tools are the same, but the cause and effect are much more direct and observable.

Central bankers around the world would love to have negative rates as a stabilizer, and in crypto, we actually implement them – successfully. In the real world, any change affects millions of people. In crypto, we can actually run all these experiments and gather the data, with real people instead of simulations, and all on a voluntary basis.

I’m convinced that we’ll learn more about how to run discretionary forms of money from quasi central banks running on top of permissionless blockchains than we did in the last twenty years of central banking. Systems like Maker (and its many competitors that are spinning up right now) will breed an entirely new class of money system designers. Within the next five years, we’ll both see a major central bank hire a stablecoin designer, and a stablecoin system hire a famous central bank economist.

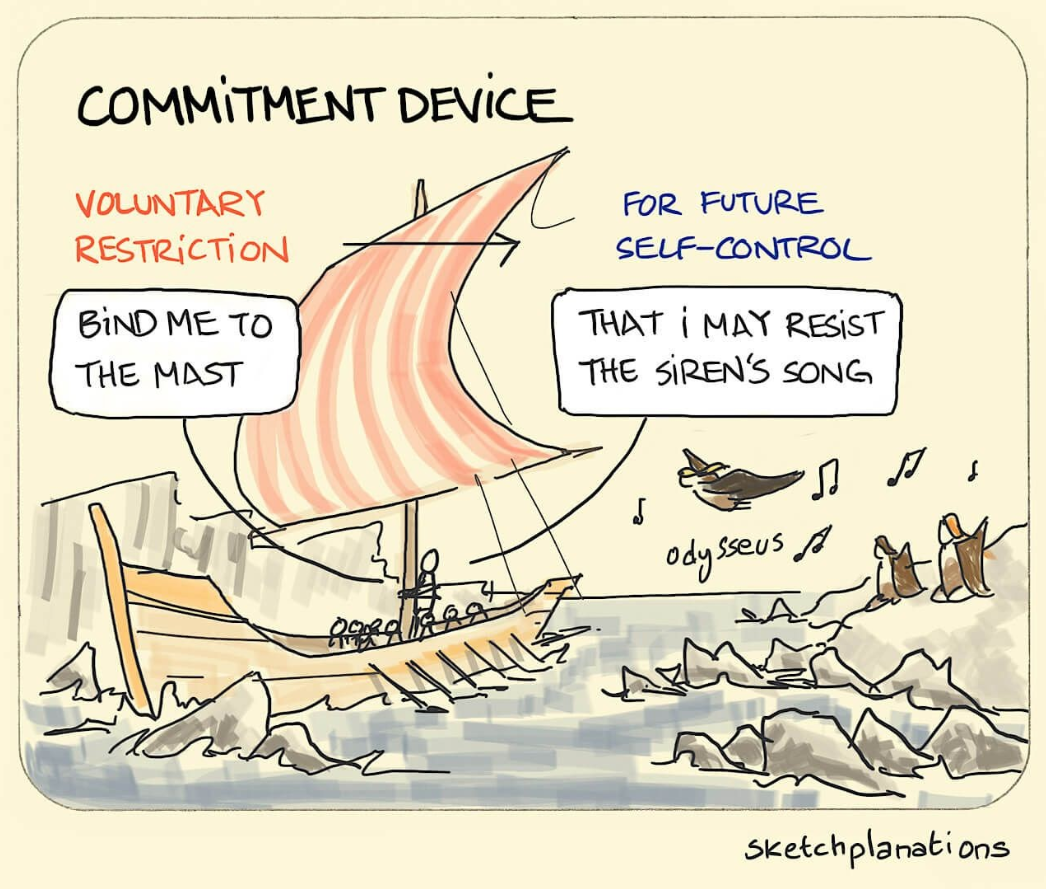

Many pundits in crypto both predict and long for, the end of discretionary monetary policy. But the real problem isn’t discretion but political influence over central banks. There is nothing wrong with managing money against a stability target. The market proves that premise correct every day. Crypto means much more experimentation with monetary rules, algorithms, targeting & stability mechanisms, with smart contracts serving as the missing puzzle piece: a commitment device.

A new generation of algorithmic central banks will be disciplined by free-market competition and shielded from government influence, made possible by a trustless base layer of collateral. The result is that discretionary money systems could, instead of being replaced wholesale by non-discretionary systems like Bitcoin, have their golden future still ahead of them.

AUTHOR(S)

THANKS TO