Governance tokens (though I prefer the term equity tokens, really) typically entitle the holder of a share of the project’s fees and some voting power in its governance.

Take for example SUSHI, the native token of the sushiswap exchange. When staked in the Sushibar contract, stakers receive fees in size of 0.05% of all trading volume. They also receive “Sushipowah” that represents voting rights in Sushiswap’s off-chain governance system.

Tokens like SUSHI are among the most hotly debated topics over the last years and divide most crypto fans and researchers into two camps. The first camp sees tokens as a liability to be minimized, often accompanied by cries of “why does project XYZ need a token?” I used to fall firmly into this first camp, but now find myself increasingly in the second, which sees tokens both as a necessity and an important incentive mechanism.

Let me explain how I changed my mind.

I’ll start by steelmanning the first camp’s thesis. It comes down to three main arguments:

- Governance itself is an attack vector because it allows bad actors to change the rules of the protocol and – in the worst-case – steal user deposits. this defeats the whole purpose of using smart contracts to begin with.

- Our goal in crypto is to replace rent-seeking companies and institutions with open and fair protocols. Extracting rent from users is regressive and violates this core value.

- Since protocols are open-source and can be forked by anyone, the equilibrium rent is always zero. It’s only a matter of time until we converge on that equilibrium, and then the value of governance tokens will likewise collapse to zero. That’s why anyone selling them today must be a scammer.

Governance and security

To make one thing very clear, I find the first argument to be highly sound. Much of the value of crypto networks and applications comes from being hard to change. This allows users to trust that the application will do what it says, and developers to build on them without platform risk.

Tacking on governance to a system that doesn’t need it turns this logic on its head. When we allow humans to change a system in a top down way, we lose the aforementioned assurances. And since some of the possible changes are very bad for users, we need to pay these governors fees in order to bribe them to prefer honest behavior over malicious one. In other words, the security model of that application changes from cryptographic to economic (guaranteed by economic incentives) – which is strictly worse.

This argument goes way back to BTC itself. Some critics point out that we pay miners a lot of money to protect the network, but the only people who can attack the network are the miners themselves! So do we actually pay protection money to these thugs?

If we could get rid of miners and save that money, that would be highly preferred. But alas, we need *human inputs* in Bitcoin to order transactions and blocks. And so we need to pay enough money to the human workers to incentivize good behavior.

Need for human input -> Need for incentive -> Need for fees

This argument holds for many systems in Defi in their current iterations. Compound or Maker couldn’t work without human input and hence couldn’t work without fees. That is because the risk from changes isn’t isolated. someone needs to control what collateral gets added because one bad piece of collateral could destroy the entire system.

The same isn’t true for Uniswap or Sushiswap. Every pool is a standalone entity. And if one pool gets drained because one of its tokens went to zero, that risk does not spread to the other pools. As a result, there is no need for governance to manage what pools can exist.

So already, some projects need human inputs to work, and those projects are naturally exempt from the arguments that fees are unethical and fees will be forked out because similar projects without fee can’t exist.

That doesn’t mean Uniswap and Sushiswap shouldn’t have a token. In fact, I will now explicitly argue that they should. Token maximalism simply shouldn’t go along with governance maximalism just because developers feel a need to give additional functionality to their tokens. Governance minimalism is still king, even if the project has a native token.

The ethics of rent

Occasionally it’s good to be reminded how all of our wealth is the result of the capitalist system. Capitalism is great because it aligns the incentives of society as a whole with the incentives of the individual. It allows people to be selfish and still benefit society, by serving each other.

I think it’s quite illogical to call people who perform a service to others (e.g. by building a crypto application) in return for some compensation “unethical”. I don’t think it’s a surprise that defi is the most rapidly innovating market I’ve ever seen. smart people have an incentive to work there because they – among other things – can get rich in the process.

If we have an ethical responsibility in this space, it shouldn’t be to minimize the rent we seek, and thereby walk away from capitalism. Instead, we should ensure that the social standards we set for this space are compatible with how humans want to behave, and funnel that energy into a better world for everyone. The mechanisms of the market (competition, open-source code, etc.) will themselves ensure over time that this rent won’t be larger than necessary.

The bootstrapping problem

The token-skeptics argue that because protocols can be forked, the equilibrium rent will be zero. I think this increasingly looks like a pipe dream for two reasons.

First, without rent, there is nothing worth forking to begin with: it’s simply too hard to compete with incumbent networks if you can’t reward your early adopters. And these rewards need to be taken from somewhere.

Proponents of the first camp will now typically say, but bitcoin got there without rent. Yes, Bitcoin got there without rent, but not without a token, and in many ways that serves the exact same purpose. Bitcoin wasn’t useful early on, but people knew if its useful later then every BTC would be worth a lot of money. And hence they bought and traded it, and in the process of doing that increased Bitcoin’s liquidity and public profile.

Based on a german fable, Baron Münchhausen pulled his own hair to lift himself from the swamp.

If you’re early to Bitcoin, and Bitcoin ever takes off, you will be rewarded handsomely. And hence there is a real incentive to be early. But if you compare that to Uniswap, Ethereum’s biggest DEX, it has no such incentive baked in. If you’re an early liquidity provider or trader to Uniswap, then you get a much worse deal: the UX is shit, the market’s illiquid, and there are no organic takers.

It doesn’t mean there can’t be early adopters, but they must find the system immediately useful to them, and that is a huge restriction for early networks. Imagine if BTC couldn’t appreciate in price, and the only people who have a direct incentive of owning it would be people who need it to make immediate transactions – it likely wouldn’t even exist today, because none of these use cases would have materialized to a meaningful degree.

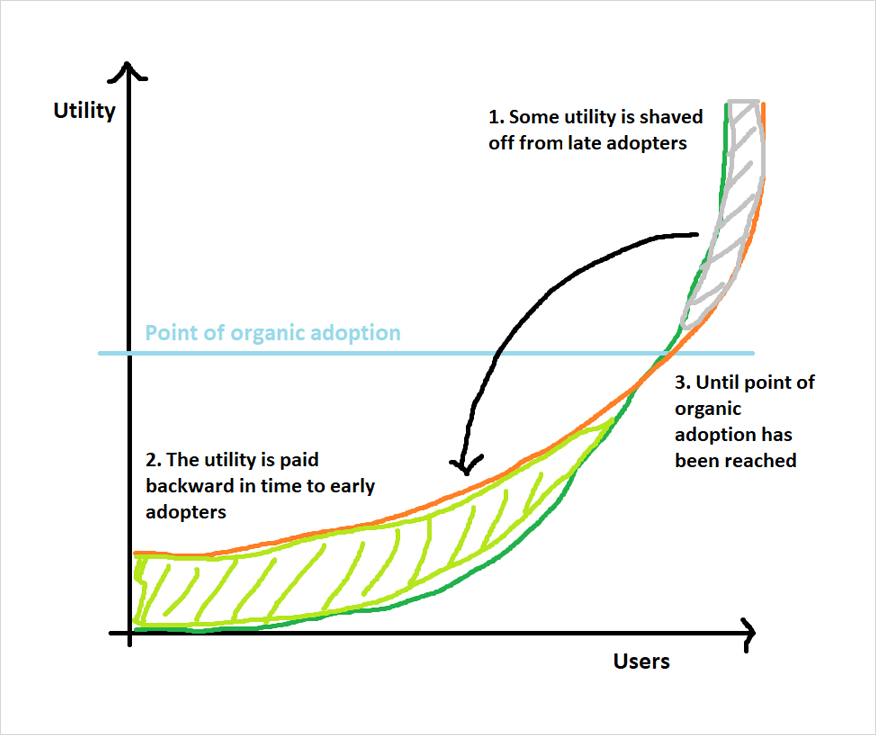

That’s why it’s so important for networks and two-sided market places to be able to reward early adopters with something taken from late adopters.

And that is why I think the generalization of mining pioneered by Synthetix and Compound is such a big deal. Projects have found a hack to bridge the difficult early adoption phase by funneling the utility of future adopters to early ones, thereby smoothing out their respective utility functions.

Attracting and retaining developers

We have touched on how capitalism works exactly because it leans into people’s self-interest. People need to be able to experiment in serving each other, and outside of fairytale socialist ideals, that simply doesn’t happen at scale when you preclude the ability to profit from your own work exclusively via some concept of equity.

This is what tokens (and pre-mines, to be precise) afford as well: They allow projects to raise money and hire developers and designers and community managers etc. most of which would not work for free.

Now people typically bring up two counterarguments, depending on what community they are from.

Bitcoiners say “but Bitcoin didn’t have a premine and look where it is today”. Bitcoin has the ambition to solve one of the world’s most fundamental problems, hard money. That allows it to attract volunteers who contribute their work for ideological reasons instead of money (and besides, most BTC contributors work on grants today). But not every project can do that, and shouldn’t have to. there are thousands of smaller problems to solve that – all taken together – can change the world just as much.

Ethereans would say, Uniswap was founded with a grant from the Ethereum foundation (which is true). But the EF’s money was itself premined, and Uniswap would never be where it is today if it hadn’t raised venture money very soon after to hire and retain more talent. These investors didn’t give Uniswap their money because they wanted to use Uniswap – a token launch was always planned from the start, it’s what made the investment and the success of Uniswap possible.

No other project since Bitcoin has managed to bootstrap itself without rewarding their early contributors AND been more than a mere copycat (thus excluding litecoin). Even Monero, which is often seen as other fair launch coin, has credible allegations of a premine via cripple mining. Maybe we shouldn’t condemn that, but simply acknowledge that very few people are willing to dedicate years of their life to a highly speculative endeavour without any financial upside.

Network effect as a moat

At this point, we have established that protocols that tokenize late adopter utility to reward early adopters will most likely outcompete protocols that don’t and rely entirely on organic growth. Now the final question is, if a project from the first category has gotten big, can someone come along and fork it to remove the fee/token, to socialize its utility?

First, remember that protocols reliant on human input can never remove the fee, because its necessary to incentivize miners/governors. That leaves projects that function without any human work necessary.

Those can still have tremendous network effect that a new fork would have to overcome.

The network effect of Maker and Synthetix, for example, exists in the form of their synthetic tokens. Any fork would start with zero collateral locked and zero synthetics in circulation.

Without a direct financial incentive, it’s incredibly difficult to get both sides of a market to stop whatever they are doing and move to a new system together. A new system, that – even if its slightly cheaper to use – would have a weaker brand, weaker liquidity, no developers, no community, no integrations with other projects, etc. Overall, I think there’s a very good chance that beyond a certain size, projects are basically resistant to forks. It’s just a matter of getting to that point.

Takeaway

Crypto is already at a disadvantage to traditional companies because everything is open source, making it harder to monetize innovation. That’s why all the highly successful crypto projects will rely on network effect, enabled by the superior properties (credible neutrality, permission access, etc.) of public blockchains, as their moat.

But new networks are extremely hard to bootstrap. Tokens, and liquidity mining in general, are a brilliant innovation in bootstrapping liquidity in two-sided market places that crypto urgently needs to overcome the network effect of incumbent networks.

Don’t just ask “why does xyz need a token?” but also “how can xyz support a token”? Because if it can, its chances of success will be greatly increased.

AUTHOR(S)