The goal for market makers in all markets is to profitably handle incoming order flow–the requests of takers to trade against their liquidity. For the naive observer, this goal seems absurdly easy. After all, clients are trading against a bid-ask spread and thus paying a demonstrable edge to the maker. Moreover, the maker often can charge fees to takers, further cementing their profitability.

The idea that takers are edge-paying clients while makers are profit-accruing enterprises is broadly true yet fundamentally wrong. My firm Three Arrows Capital and several other nonbank participants made significant sums over several years in the Foreign Exchange markets by exploiting these types of naive assumptions by banks about market structure.

Where are the makers’ yachts?

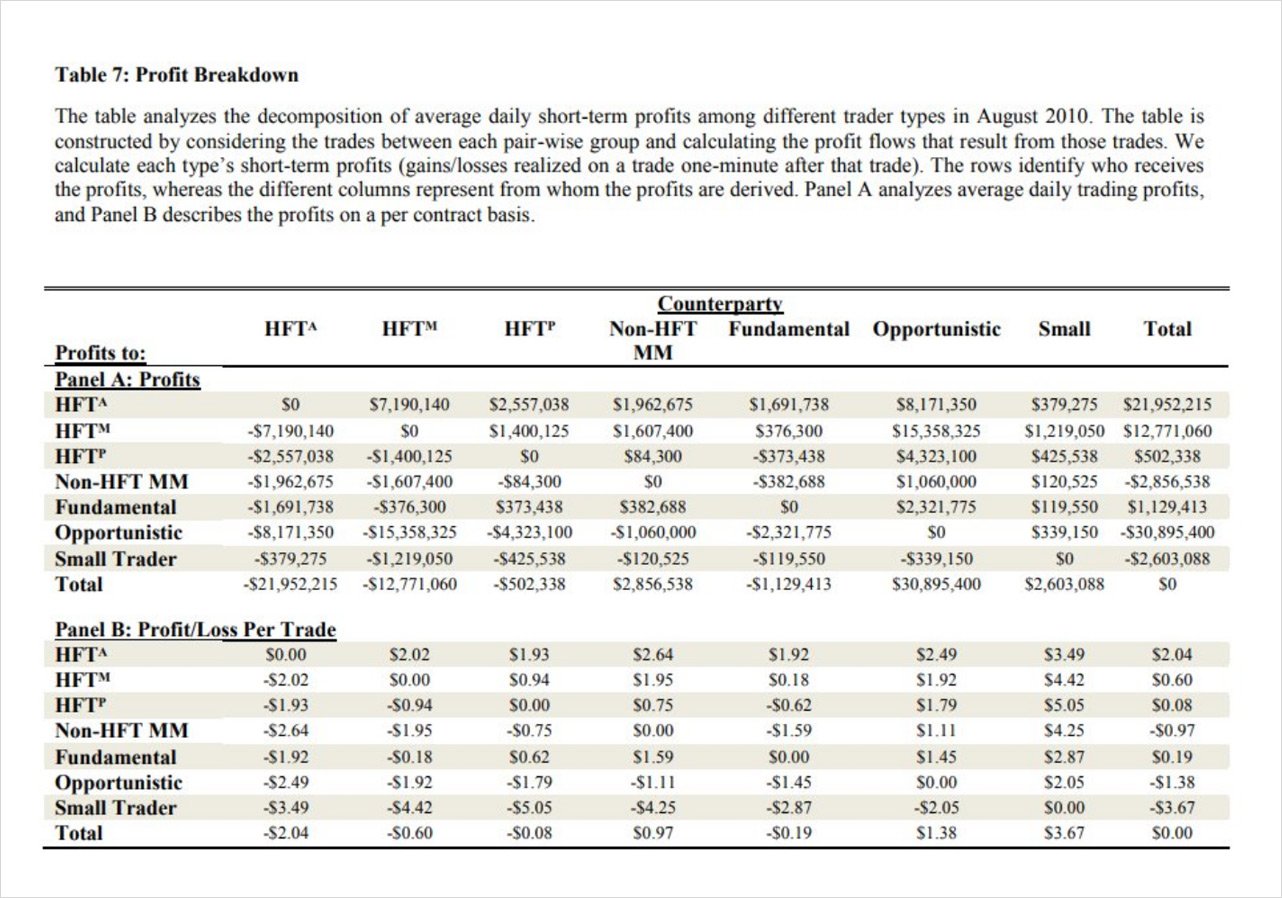

This table from the CFTC shows the short-term profit & loss on ES (SP500 futures on CME) categorized by different counterparty types, both HFT and non-HFT.

Note that aggressive HFT earns $22mill, mixed HFT $13mill, passive HFT $0.5mill. Biggest loser is from Opportunistic counterparties, at -$31mill.

The first question you would obviously ask is–why are the passive HFTs so poor and why are the aggressive HFTs so rich? Aren’t the aggressive firms paying the bid/ask spread while the passive firms earning it? Aren’t takers customers and makers businesses? Moreover, why are opportunistic traders so incredibly unprofitable on short time scales?

In a word, information. The average taker might have no alpha, but the sharpest takers fundamentally have much more information than makers. I alluded to this in my previous article on whether maker rebates are a free lunch, but the basic idea is simple; takers do not need to trade. They can lie in wait for opportunities to pop up and trade only when those conditions are met. In contrast, makers must constantly make their liquidity available to whoever wishes to trade against it.

Consider the card-counting blackjack bettor against the casino. The casino welcomes betting action from everyone, and most people lose money to it. Yet it just takes a few large card-counters to bankrupt the house, and casinos spend significant resources making sure that such betting action is not taking place.

In the markets, sharp takers cannot be thrown out of the premises. They can freely trade as peers to the makers. No matter what the fee or perceived spread is, these numbers are irrelevant as the taker can just put those numbers into their models accordingly. The higher the fee and wider the spread, the less frequently they’ll trade. This then drives up costs for everyone.

Opportunistic traders, despite the word “opportunistic” making it sound like they should be informed traders, actually lose the most on short time scales because they are not even trying to win at that granularity. They have no knowledge of the price action of the next few seconds or minutes, but simply want to get filled on their position. Their holding period may be one thousand to one million times longer than HFT timescales. They are trading positionally rather than tactically.

How does one create toxicity?

The flow from sharp takers is called toxic because the maker will find themselves to be out-of-the-money nearly immediately after the fill. It is like a radioactive piece of matter where as soon as one participant has the risk, they immediately wish to pass it off to another.

Takers generate toxic flow through two main ways: latency and coverage. Latency means they have faster connectivity to other venues with similar products, and so they can aggressively take against makers knowing that the market is already higher or lower elsewhere. Coverage means they are connected to more venues than makers, so they are aware of activity in markets that makers cannot access. Such examples could include an OTC buy that plans to lift every offer on every venue.

In fact, if you were to ask the top HFT firms, they would tell you that their market making strategies make minimal profits on their own but that the real profits come from being able to use that information in taker strategies. For instance, on some venues, the fill information is disseminated earlier than the publication of time and sales of done deals. This means that the only way to buy yourself a latency advantage is to first get picked off in small size as a maker yourself.

To give 2 concrete examples of toxic flows (theoretical examples):

- A taker which is integrated with 5 venues (exchanges, OTC desks etc) has an aggregate view of the available liquidity with each venue/counterparty. They see that offers on 3 major exchanges are being lifted aggressively, and offers on venue 4 are thinning out/being pulled. However on venue 5, prices have not yet moved. They immediately take that liquidity on the offer and repost it higher, being taken out of their risk immediately and capturing a small spread.

- A taker simultaneously buys/sells across multiple venues at once in sizes large enough to move prices. As liquidity has a “multiplier effect” (where one can source liquidity from one venue and deploy it on a second venue), it means a lot of hedges for market makers disappear. As a result, liquidity providers will need to aggressively skew their prices to get their deltas back, which in turn provides liquidity for the taker to exit into.

What does this mean for AMMs?

Just as in traditional markets, we should expect that sharp traders against AMMs will end up making more money than LPs in AMMs themselves. This may still be ok, as long as AMMs can figure out how to keep costs low for non-sharp traders and high for sharp ones. This became possible in FX with the advent of flow characterization and segmentation by makers. What they did was give makers a way to tag profiles of various takers and to turn off the ability of those takers to trade against them if the flow was unattractive to the makers. Makers could then continue quoting tight to soft clients while mitigating losses from sharp ones. In FX, the rise of ‘last look’ liquidity also means that LPs could/can provide non-firm quotes, giving the option to the liquidity provider to accept, reject or re-quote a price prior to execution. As being an LP can be compared to providing a continuous stream of short term options to takers, last-look liquidity offers an option back to LPs in order to protect themselves. But needless to say, this does not exist in AMMs given pricing is deterministic according to a formula (e.g x*y=k).

Hence given the lack of sybil defense in crypto markets, minimizing LP losses from toxic flows would be a difficult approach. Faster oracles, more robust and dynamic calibrating of pricing parameters, and systematic reclaiming of profits from sharp takers are likely part of the solution.

With that said, one distinction between toxic flow in traditional CLOB/FX and in AMMs is that: in traditional markets, what makes the flow toxic is that LPs are unaware that they may be providing liquidity at a loss. Whereas in crypto/AMMs, risks of impermanent loss to LPs are known, and looking at on-chain analytics, we can even go as far to say/generalize that an overwhelming majority of flows which gets executed on AMMs are toxic in nature (arbitrage driven). Fees are one (key) part of the equation which has already been addressed (without fees, LPs will always be worse off vs a buy-and-hold portfolio). However there may exist a spectrum of fees (for a given price drift) where LPs can realize a higher rate of return vs a buy and hold portfolio. Holding everything else constant, this is what matters to LPs, and is the equivalent of the bid-offer spread. Outside of fee constants, other parameters may include the shape of the bonding curves, the (adjustable) mid-point of the bonding curves, and the pool compositions (away from constant 50/50 liquidity).

In the end, whether makers are automated or non-automated in nature, they cannot avoid their liquidity being used to generate alpha for sharp takers. The sustainable market ecosystems for AMMs will be ones where passive makers can still outperform buy-and-hold and benign takers can still execute at reasonable prices, but the question of how to get there in DeFi is still largely unsolved.

AUTHOR(S)